Teaching Portfolio

An evolving record of teaching and educational scholarship

Teaching Philosophy Statement

I honestly can’t imagine ever growing tired of learning and teaching about the human body. I am mesmerized by every detail, from how our tissues develop and grow to the way they are affected by aging and disease. This insatiable curiosity and love for anatomy underpins every lecture and fuels me with tireless energy during every lab, but knowledge and enthusiasm are not enough to be an exceptional educator. My approaches to teaching and my beliefs about how post-secondary students approach learning have evolved immensely since leading my first formal lesson (if you’re curious, I was 10 years old & the topic was how to tie nautical knots), but I aim to capture in this statement a snapshot of the core principles upon which my current teaching philosophy is built.

1) Teaching and learning should both be approached as perpetual works in progress. The idea that I will never “master” teaching used to terrify me, but instead of succumbing to this fear I have embraced ‘lifelong learning’ as a core principle of my teaching philosophy. Learning to teach is a lifelong process and therefore the pursuit of perfection is neither attainable nor entirely desirable — the ‘perfect’ teaching approach for one student might disenchant another, so as educators we must be willing to learn from our students as much, if not more, than they learn from us. If we can embrace the highs and lows of learning to teach without getting discouraged by the inevitable lack of predictability, I strongly believe that we are better positioned to help instill the same type of growth mindset in our students. Anatomy is notoriously challenging partly because it requires learning a whole new language, but like any language it can become second nature with diligent practice and patience. Some students are especially resistant to this reality (e.g., chronic high achievers with impossibly high standards, whether self-imposed or otherwise), which is ironically the same type of student with which I relate most closely. Fortunately, my firsthand experience as a persistent perfectionist makes me uniquely qualified to understand why so many students struggle to embrace the “long game”. I pride myself in openly sharing my own challenges to reassure my students that they are not alone.

2) Take chances. Make mistakes. (Messiness optional). Like many 90s kids, The Magic School Bus holds a special place in my heart, but beyond nostalgia I genuinely believe that Ms. Frizzle had the right idea. I have observed that many post-secondary students approach anatomy with brute force rote memorization in hopes of scoring top marks on exams, irrespective of long-term retention. I try to instill in my students the importance of making mistakes while they learn because predictions (i.e., taking chances) that turn out to be wrong (i.e., making mistakes) are an irrefutably important part of the learning process. When students embrace mistakes rather than fearing them and find the courage to challenge themselves, learning has the potential to be both less stressful and more impactful. Since this is a difficult transition in mindset for most students by the time they reach university, I include frequent low-stakes and/or zero-stakes opportunities for students to embrace ‘failure’. Another benefit of normalizing the effortful and uncertain nature of learning in a safe environment is that students seem willing to assume a more active role in the process. I try to further destigmatize mistakes by shamelessly owning up to my own. To err is human, after all.

3) We owe it to ourselves, and to our students, to rekindle the joy of learning. As a child, I vividly recall sprinting home from school and peppering my parents (or anyone else who would listen) with all the fascinating things I had learned at school:

The reason leaves turn colours and fall off trees in the autumn.

The difference between rotation and revolution of the Earth.

Why you can’t divide by zero (still not convinced I fully understand this one…)

I often ponder exactly when we start to lose the sense of wonder and joy we felt as children when we learned something new, and I suspect one of the major factors is a lack of opportunity to ‘play’. Since play is intrinsically motivated and prioritizes the process over the result, it offers a unique environment in which learners can take in information in a less inhibited state. I incorporate serious play and game-based learning approaches into my classes where feasible (and offer supplemental gamified activities when it is not) to give students an opportunity to genuinely enjoy even a tiny portion of the learning process. Game-based learning also engages the concept of a ‘magic circle’ wherein the boundaries between game and reality are clearly defined and ‘players’ are safe to venture judgement free outside of their comfort zones. The growing levels of stress and anxiety I have observed in students gives me even more reason to continue embracing game-based learning in my courses. Learning anatomy will never be “easy”, but there’s no reason it can’t be fun!

By leveraging a combination of these core principles, my goal as an educator is to inspire and empower my students to discover what piques their own insatiable curiosity, whether it’s anatomy or Shakespearean literature. Few things bring me more joy than seeing students enthusiastically embrace the learning process and experience those authentic ‘aha’ moments when things click into place. There is no perfect pedagogical formula for teaching anatomy, but I sincerely look forward to taking chances, making mistakes, and having a LOT of fun for many, many years to come.

Teaching Impact

Teaching Experience (Including Enrollment & Contact Hours)

1: Course Coordinator & Instructor; 2: Course Instructor; 3: Anatomy Component Lead; 4: Laboratory Demonstrator; 5: Lecturer; 6: Graduate Teaching Assistant

Teaching Effectiveness (Including Course Evaluations)

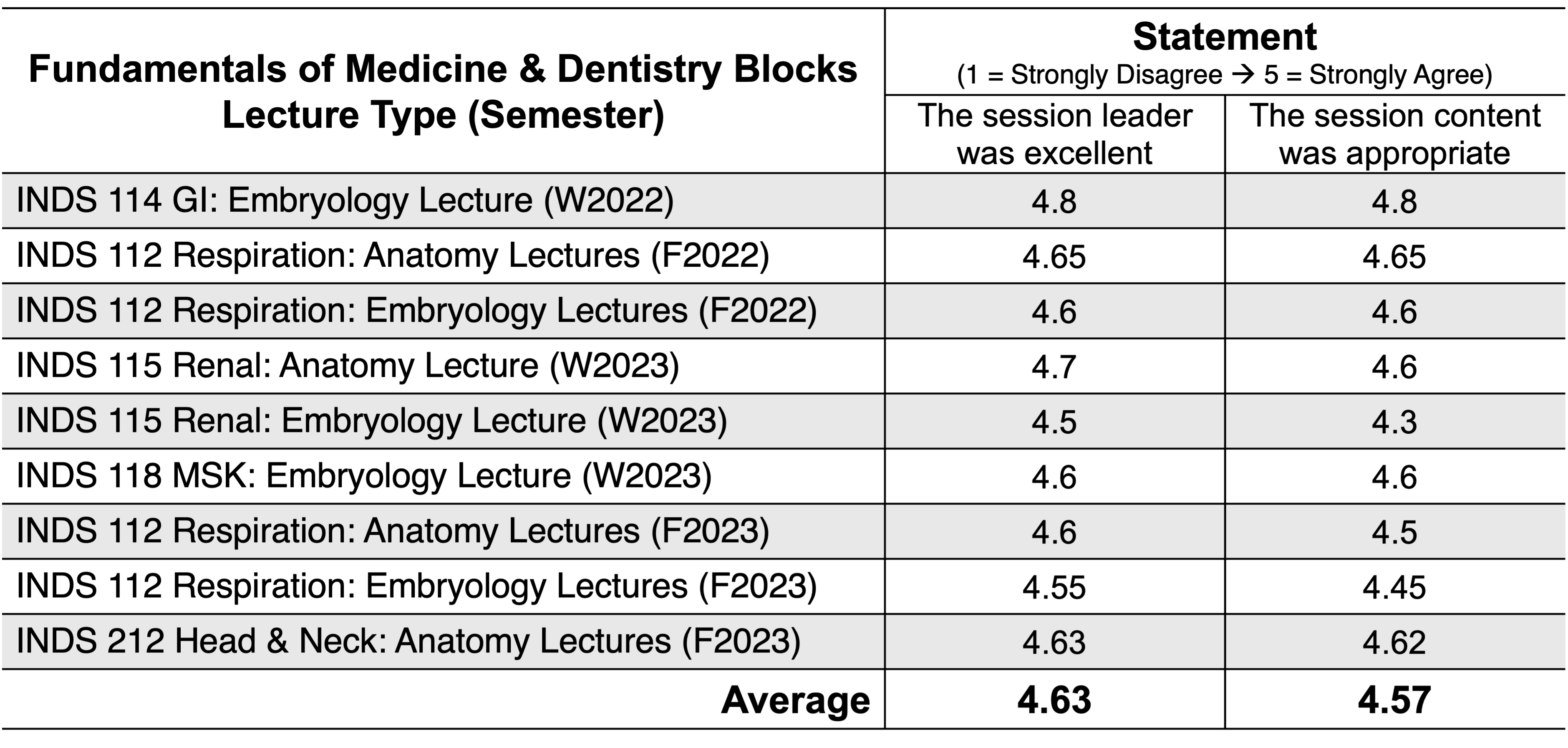

All ratings are on a scale from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree)

Course: course mean; Department: department course mean in the corresponding semester

Representative Student Comments

Although the content is heavy and can seem very overwhelming, Dr. Stiver does an amazing job and finds ways to continuously engage us in the content. For instance, when it got to studying for the final, I was so surprised by how much I actually remembered from previous content that we were tested on at the beginning of the semester and I think this is in great part due to Dr. Stiver who challenges us with clinical cases that make us think critically about all the content.

Dr. Stiver always encouraged us to speak up in class and reminded us that its okay to make mistakes. While in the beginning of the semester, we were definitely more shy and didn’t participate so much, by the end of the semester I find that everyone become comfortable around each other and this in my opinion is due to Dr. Stiver’s continuous encouragement.

Dr. Stiver is passionate about neuroanatomy and she transmits her passion to us when explaining different concepts. Neuroanatomy is a pretty complex subject but Dr. Stiver delivered the material amazingly and I learned a lot. She was always there to answer our questions whether it was during lectures, on the discussion boards, during her office hours, or during the lab. She always pushed us to ask questions and participate in class and always had a great energy. Dr. Stiver encouraged us throughout the semester to continue to work hard and reinforced the fact that we are intelligent students and that we are very capable of doing well.

Dr. Stiver is one of the best university teachers that I would probably ever encounter at McGill for so many reasons. Firstly, she is so knowledgeable in neuroanatomy. Her lectures are easy to understand and she answers to our questions right away in class and outside of class all the time. Secondly, she is so caring as a teacher. She always checks on how we are doing before class and put a lot of effort to cheer us up when our class is feeling a bit down. She has a big heart to help the students succeed and is always available to help. Thirdly, she did a great job to make this class fun and exciting despite the contents being a bit heavy. For example, we had a question game before both of our midterms which was stimulating and engaging. She also reads riddles before labs to engage us. She uses her strength which is being creative to engage the class in this course. By doing so, she successfully made a neuroanatomy class enjoyable and interesting. I think I had a good giggle with my classmates in every single one of her lectures and labs because she is very bubbly and bright. Thank you for making my days more joyful. I also appreciated when you were so transparent about how you feel. It made me feel like it’s okay to be human and not always hide how I feel. I know that there were days that were harder for her to teach but she was able to deliver an excellent lecture and I respect her a lot. I wish that she has less on her plate so that she can have a bit more rest for the work she puts in this class.

Dr. Stiver is an amazing teacher. Throughout the course, she has demonstrated an unparalleled commitment to fostering a deep understanding of the subject matter. Her teaching style is not only engaging but also tailored to meet the diverse learning needs of students. The clarity with which complex neuroanatomical concepts are conveyed reflects Dr. Stiver’s profound knowledge of the subject. Furthermore, her passion for the intricacies of neuroanatomy is contagious, creating an inspiring learning environment. What truly sets her apart is her dedication to student success. She goes above and beyond to ensure that each student comprehensively grasps the material, offering additional resources, clarifications, and encouragement when needed. Her approachability and willingness to address questions demonstrate a genuine concern for the academic growth of her students. Her motivational speeches prior to our evaluation also offered some needed reassurance and I looked forward every lab to see what the next neuroanatomy joke would be.

Reflection

I would be remiss not to address the slight decrease in student evaluation scores between F2022 and F2023. Despite making very few changes to the content or format of the course, it appears that my delivery of the content was not as effective as the previous semester and is likely in part due to the volume of additional teaching that I had to take on in the Fall semester, including an intensive Block in Fundamental of Medicine & Dentistry. I acknowledge that I will need to make some adjustments moving forward if I am to sustain this intensity of workload in the long term. The majority of student comments were very positive and encouraging, though a few specifically expressed frustration about a typo on their midterm exam [likely the main reason for the substantial drop in the “fair evaluation method” score] and displeasure with the fact that lectures were scheduled in the late afternoon that led to a majority of students skipping live lectures in favour of lecture recordings.

Representative Student Comments

This is one of the best, if not the best, course I have taken at McGill. Other professors should look to [co-instructor] and Dr. Stiver as an example for how to design and teach a course. I think all students could feel that they really cared about our learning and were doing their best to make the content digestible. In return, we felt motivated to give our best effort. They were always so approachable and available to ask questions or even just chat about how we were doing and our thoughts on the course. Expectations were crystal–clear and all the material was presented in a very organized way.

Dr. Stiver was an excellent lecturer and was clear about the course material. Went through everything that was confusing slowly and took time to explain in different ways it something didn’t make sense. Made fun activities to help with our learning.

Reflection

I co-taught this course in W2022 and W2023 with a different colleague in each year. I am relatively new to co-teaching a course and it certainly took some time to adjust. In particular, it was occasionally to reconcile differences in approaches to teaching and assessment. In both years, we divided the course content between the instructors and created collaborative review sessions in preparation for the midterm and final exams. There were also difficulties that arose when students inevitable started comparing between the two instructors, but it was also a valuable opportunity to check my ego and refocus my priorities as an educator.

Representative Student Comments

This is the first time embryology made sense to me; this is the first time embryology helped me understand anatomy. I usually don’t get embryo and don’t study it really much for exams, so my previous embryo knowledge is rather limited, but everything was beautifully explained, it doesn’t assume a lot of prior knowledge, and it really helps understand body cavities, orientation of organs and vessels, spatial organization, etc. and this is probably save me a lot of anatomy review time. Thank you SO much for your passion, enthusiasm and kindness during the lecture. The annotations also help follow a lot. My only regret is not having had you as a lecturer for all the other embryo lectures because other profs were very good, but you are simply amazing!

Dr. Stiver is an incredible teacher and her first time teaching embryology was really a success. I loved how she used annotation on her tablet to point out different structures on the slides and how she demonstrated different twisting/movements using hand motions. Her slides are also very clear, comprehensive, and clean. Overall a great lecture and lecturer!

Of course the lecture content is very challenging, especially if coming from a non-anatomy background, but you can really tell just how much the teacher cares about our understanding of the material. She color codes the slides, she adds funny anecdotes, and she’s so passionate about the lecture topic. Even though I am thoroughly confused and have to go over the lecture at home, it’s honestly really nice to come to class to take notes with her as the lecturer.

Reflection

Having now taught in 5 different Fundamentals of Medicine and Anatomy (FMD) blocks, I have gained a much better appreciation for how to best integrate the anatomy and embryology content and contextualize it with respect to clinical considerations. Although I have countless ideas for how the material could be presented in more creative and engaging ways, I have learned to accept that the Medicine and Dentistry curricula are jam-packed as it is so there is not as much room for innovation. Instead, I seize the opportunity during dissection labs to try new approaches and integrate optional activities (e.g., DIY bellringer exams, interactive extraocular muscle models).

Teaching Awards

- 2023 Faculty Award for Teaching Innovation (Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, McGill University)

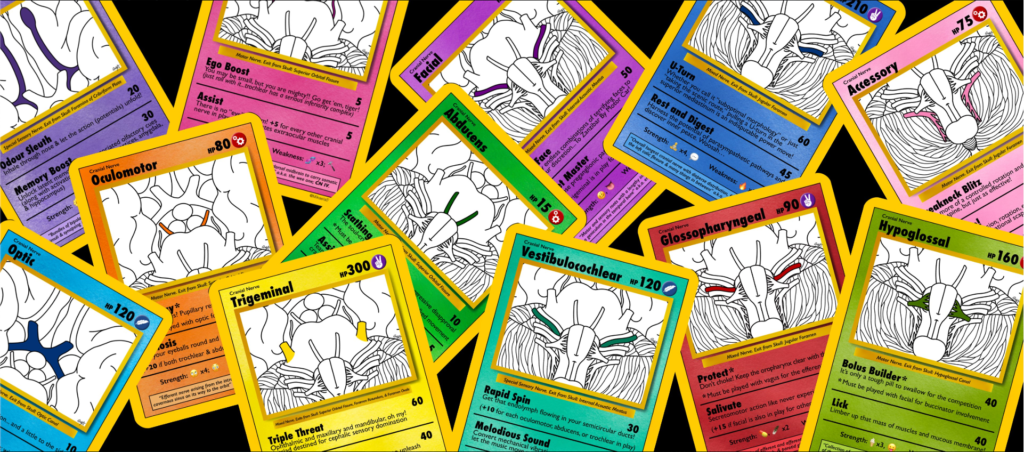

“Prof. Stiver integrated gamification and serious games into ANAT 323 Clinical Neuroanatomy by creating Pokémon-inspired neuroanatomy trading cards to teach the 12 cranial nerves, as well as adapting popular games like HedBanz and Kahoot! to advance learning”

"Thank A Prof" Program

Teaching and Learning Services at McGill University created the “Thank a Prof” program so students can thank professors who have made a difference in their lives, no matter how big or small! Click below for an example of a letter I received during the 2023/2024 academic year:

Recent Educational Scholarship & Projects

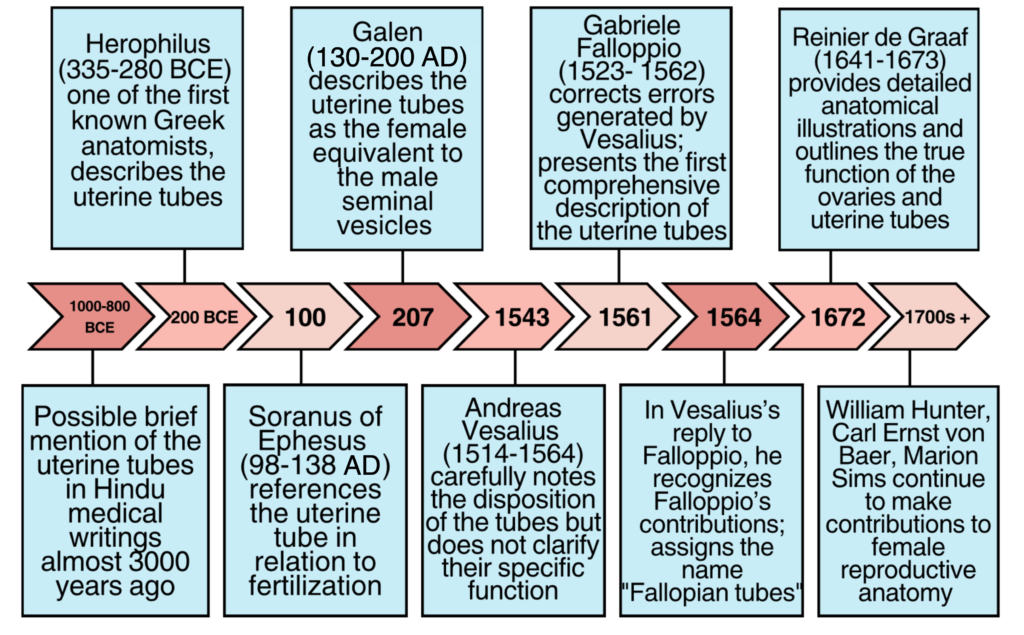

In collaboration with Dr. Charys Martin (Western), we are examining how educators and clinicians use anatomical eponyms. This research, along with the creation of an online educational resource, is informing the development of a serious board game aiming to teach the history of commonly used eponyms and encourage the adoption of descriptive terminology — an important step in decolonizing the field of anatomy and increasing accessibility for the general public.

More information:

(COMING SOON)

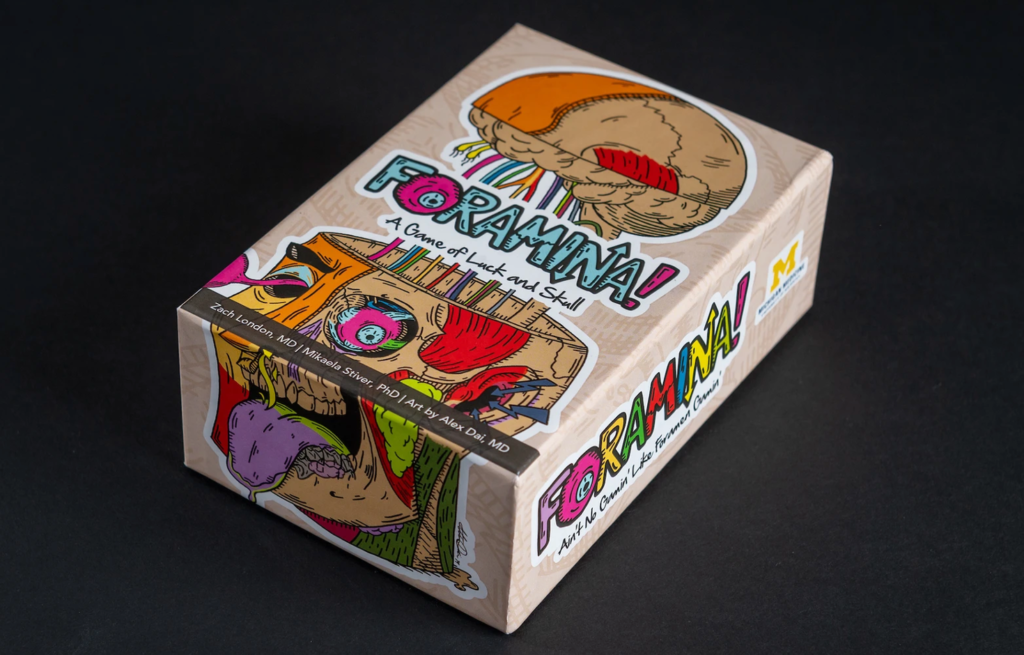

I connected with Dr. Zach London on Twitter (X) over a mutual love of board games and all things neuro. “Foramina!” is a semi-serious game celebrating cranial nerves and their corresponding foramina in the base of the skull. The game can be played without in depth knowledge of neuroanatomy, but all of the details are 100% accurate. To date, we have sold over 220 copies in 12 countries (3 continents).

More information:

https://www.neurdgames.com/foramina

As someone who grew up with what I perceived as ZERO artistic talent, I am often surprised that drawing plays such a central role in my teaching! Influenced by the way I first learned anatomy with Dr. Lorraine Jadeski (Guelph), I have created a range of simple templates to help my students follow along with neuroanatomical pathways and visualize how symptoms and deficits are associated with different lesions. My templates are all distributed under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

I was recently approached by a Year 2 medical student for whom drawing has played a key role in learning anatomy. We are in the process of developing & assessing the efficacy of interactive MSK drawing workshops for Year 1 medical students.

The Global Neuroanatomy Network (GNN) is an online resource repository and community of practice specifically designed for neuroanatomy educators. This project is funded by an Innovations Program Grant from the American Association for Anatomy (my first grant as a Co-PI!) and represents an extensive international collaboration involving 23 anatomists, clinicians, and researchers from 22 countries (5 continents).

More information:

https://globalneuronetwork.org/

The GAMER (Games And Medical Education Research) Collaborative is a non-hierarchical group of medical educators interested in game-based learning. I have been part of this community of ~150 members (and growing!) since 2021 and have since worked on several review papers and delivered workshops with members from all over the world. Please get in touch if you would like to join our Slack channel — the more the merrier!

More information:

https://www.mededgamer.org/home

In Fall 2021, I served as an advisor on this UBC Certificate in Biomedical Visualization and Communication final capstone project alongside the UBC Hackspace for Innovation and Visualization in Education (HIVE). This capstone project (by Alexia LaLande, Winnie Lin, Linda Ding, & Cat Lau) involved creating a card game that could be played by anyone and serve as a valuable review tool for medical students. They also designed wireframes for future AR integration.

More information:

https://www.thegamecrafter.com/games/gut-it-out

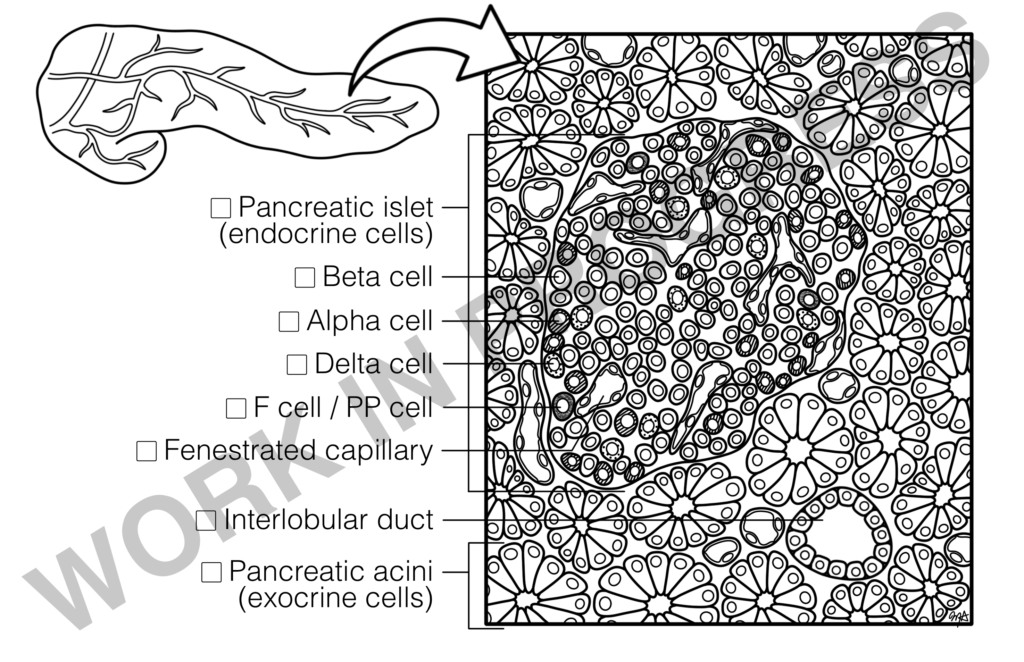

Driven by a shortage of resources available for teaching and learning histology, Dr. Karen Pinder (UBC) and Dr. Tamara Franz-Odendaal (MSVU) received funding from the American Association for Anatomy to create the first ever Histology Colouring Book. I have had the privilege of contributing as the Medical Illustrator for this project and am currently completing the last of over 100 line drawings depicting all aspects of histology!

More information:

https://histologycoloringbook.com/

I created this set of 12 cranial nerve cards, drawing inspiration for the design and elements from trading card games like Pokémon. I strongly believe that students are more motivated and engaged when they are willing to let their guards down and play — if an 8-year-old can recite over 100 ‘Pocket Monsters’ and how they interact with one another, I have every faith that university students can master 12 cranial nerves! So far, I have sold over 420 sets in over 20 countries (6 continents) and distributed dozens of free digital copies upon request.

More information:

https://www.thegamecrafter.com/games/

cranial-nerve-cards

I endeavour to incorporate games and game elements into my teaching wherever they can be suitably used to meet learning objectives. A simple example is using ‘randomizer’ wheels to facilitate review (e.g., “Clinical Neuroanatomy Terminology Randomizer Wheel of Excitement”: https://wheelofnames.com/u96-x65) or to help guide them in creating their own clinical vignettes (e.g., “Neuroanatomy Lesion Symptom Randomizer”: https://wheelofnames.com/5ds-ufz). Both of these wheels can be copied, adapted, and saved online.

Student Supervision (Educational Research @ McGill University)

Taliah Hyjazie (January 2024 – Present)

Volunteer research student [MDCM]

“Exploring the Efficacy of Interactive Drawing Workshops on Upper Limb Anatomy for First-Year Medical Students”

Mikaela-Angellika Andreadakis (September 2023 – Present)

ANAT 396 student & volunteer research student [BSc]

“Ending the Eponym Epidemic: Exploring Game-based Approaches to Encourage use of Descriptive Terminology”

Kasra Borjian (April 2023 – Present)

Volunteer research student [BSc PT]

Working with Merrill Green: “Identifying gaps in vestibular education: perspectives from McGill University medical students, residents, and affiliated physicians”

Merrill Green (January 2023 – Present)

ANAT 396 student & volunteer research student [BSc & MSc]

“Identifying gaps in vestibular education: perspectives from McGill University medical students, residents, and affiliated physicians”

Melanie Meilayi Abudukebier (September 2022 – December 2022)

ANAT 396 student [BSc]

“Scoping Review of Tabletop Serious Games in Medical Education”

Publications

- Edwards SL, Zarandi A, Cosimini M, Chan TM, Abudukebier M, Stiver ML. Analog serious games for medical education: a scoping review. Academic Medicine. (conditionally accepted)

- Edwards SL, Gantwerker E, Cosimini M, Christy AL, Kaur AW, Helms AK, Stiver ML, London Z. Game-based learning in neuroscience: Key terminology, literature survey, and how to guide to create a serious game. Neurology® Education. 2023; 2(4): p.e200103. https://doi.org/10.1212/NE9.0000000000200103

- Stiver ML, Mirjalili SA, Agur AMR. Measuring Shear-Wave Velocity in Adult Skeletal Muscle with Ultrasound 2D Shear-Wave Elastography: A Scoping Review. Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology. 2023; 49(6): 1353–1362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2023.02.005

- Barton MJ, McCombe C, Todorovic M, Stiver ML, McMonagle B. Herpes zoster isolated in the glossopharyngeal nerve: a case report and literature review. Australian Journal of Otolaryngology. 2022; 5: 7. https://doi.org/10.21037/ajo-21-29

- Stiver ML, Bradshaw L, Breinhorst E, Agur AMR, Mirjalili SA. Three-dimensional muscle architecture of the infant and adult trapezius: a cadaveric pilot study. Anatomy. 2021; 15(1): 26–35. https://doi.org/10.2399/ana.20.828627

- Stiver ML, Cloke JM, Nightingale N, Rizos J, Messer W, Winters BD. Linking muscarinic receptor activation to UPS-mediated object memory destabilization: implications for long-term memory modification and storage. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2017; 145: 151–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlm.2017.10.007

- Zwicker JG, Miller SP, Grunau RE, Chau V, Brant R, Studholme C, Liu M, Synnes A, Poskitt KJ, Stiver ML, Tam EW. Smaller cerebellar growth and poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes in very preterm infants exposed to neonatal morphine. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2016; 172: 81–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.12.024

- Stiver ML, Kamino D, Guo T, Thompson A, Duerden EG, Taylor MJ, Tam EW. Maternal postsecondary education associated with improved cerebellar growth after preterm birth. Journal of Child Neurology. 2015; 30(12): 1633–1639. https://doi.org/10.1177/0883073815576790

- Stiver ML, Jacklin DL, Mitchnick K, Vicic N, Carlin J, O’Hara M, Winters BD. Cholinergic manipulations bidirectionally regulate object memory destabilization. Learning & Memory. 2015; 22(4): 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1101/lm.037713.114

Professional Growth / Development & Service

Conferences, Workshops, & Certificates

Conferences

Attending local, national, and international conferences has afforded me the opportunity to meet anatomists around the world, build and strengthen my network, establish collaborations, and present research to get feedback from my peers. Many of these conferences included focus sessions and workshops on various topics in anatomical and medical education, allowing me to stay up-to-date with pedagogical best practices and learn about new, evidence-based teaching approaches.

- 28th Annual Conference of the International Association of Medical Science Educators (IAMSE 2024); June 2024 in Minneapolis, MN

- Anatomy Connected 2024 (American Association for Anatomy); March 2024 in Toronto, Canada

- Anatomy Connected 2023 (American Association for Anatomy); March 2023 in Washington, DC

- 20th Congress of the International Federation of Associations of Anatomists; August 2022 in Istanbul, Turkey [virtual meeting]

- American Association for Anatomy Annual Meeting at Experimental Biology; April 2022 in Philadelphia, PA

- 37th American Association of Clinical Anatomists Conference; June 2020 [virtual meeting]

- 2020 Rehabilitation Sciences Institute Research Day; May 2020 in Toronto, Canada

- American Association for Anatomy Annual Meeting at Experimental Biology; April 2020 [virtual meeting]

- 16th Annual Conference of the Australian and New Zealand Association of Clinical Anatomists; December 2019 in Perth, Australia

- 19th Congress of the International Federation of Associations of Anatomists; August 2019 in London, UK

- 36th American Association of Clinical Anatomists Conference; June 2019 in Tulsa, OK

- 2019 Rehabilitation Sciences Institute Research Day; May 2019 in Toronto, Canada

- 45th Annual Department of Surgery Gallie Day; May 2019 in Toronto, Canada

- 35th American Association of Clinical Anatomists Conference; July 2018 in Atlanta, GA

- 2018 Rehabilitation Sciences Institute Research Day; May 2018 in Toronto, Canada

Specialized Conferences & Workshops

- Anatomy Education Research Unconference; June 2023 in Toronto, Canada

- An informal, participant-driven meeting offering an opportunity to exchange ideas, strengthen support networks, and candidly discuss topics currently affecting anatomical educations

- Anatomy Education Research Institute; July 2022 in Indianapolis, IN

- Intensive four-day conference partnering leaders in medical education research with mentees interested in improving their teaching and educational research skills

Teaching Certificates

- Advanced University Teaching Preparation Certificate — University of Toronto; 2019

- 10 workshops (2 hours per workshop), teaching practicum (microteaching sessions), teaching dossier review, & written reflection assessing the value and impact of the certificate program

- Graduate Student Teaching Development Certificate — University of Guelph; 2016

- 12 hours of participatory workshops and/or conferences

Professional Memberships

- International Association of Medical Science Educators (2023 – Present)

- Australian and New Zealand Association of Clinical Anatomists (2019 – Present)

- American Association for Anatomy (2018 – Present)

- American Association of Clinical Anatomists (2018 – Present)

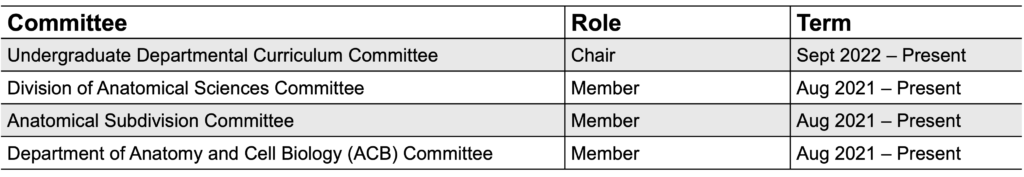

Departmental Committees

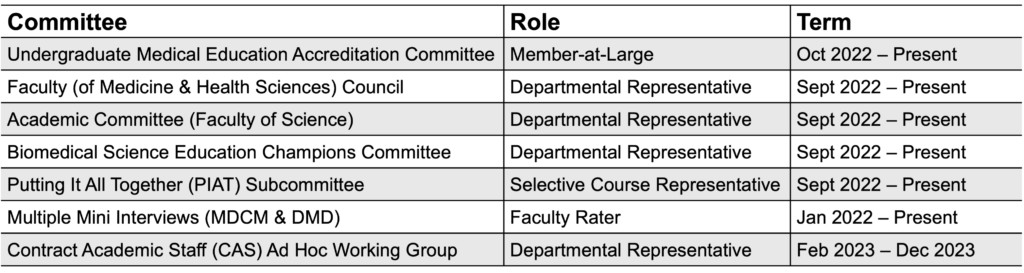

Faculty and School Committees / Activities

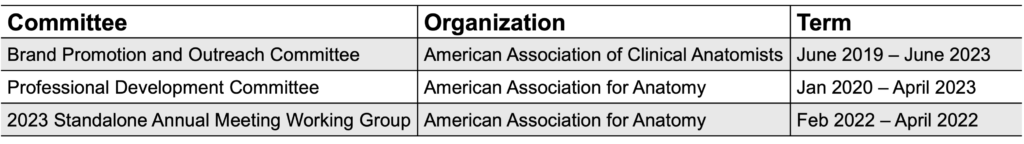

Professional Organizations

Exemplar Teaching Materials

- “The Great Musculoskeletal Mystery (Part 1)” anatomy lab activity [U1 Anatomy & Cell Biology students (ANAT 314: Human Musculoskeletal Anatomy)]

- Cranial Nerves (Part 2) lecture slides [U1 PT, OT, Kinesiology & Physiology students (ANAT 316: Clinical Human Visceral Anatomy)]

- Sensory Clinical Cases & Pain lab manual [U2 PT & OT students (ANAT 323: Clinical Neuroanatomy)]

- Pharynx and Larynx dissection lab outline [Year 2 Medicine & Dentistry students (INDS 212: Human Behaviour)]